Students find learning about electric motors difficult because:

- They find it hard to predict the direction of the force produced on a conductor in a magnetic field, either with or without Fleming’s Left Hand Rule.

- They find it hard to understand how a split ring commutator works.

In this post, I want to focus on a suggested teaching sequence for the action of a split ring commutator, since I’ve covered the first point in previous posts.

Who needs a ‘split ring commutator’ anyway?

We all do, if we are going to build electric motors that produce a continuous turning motion.

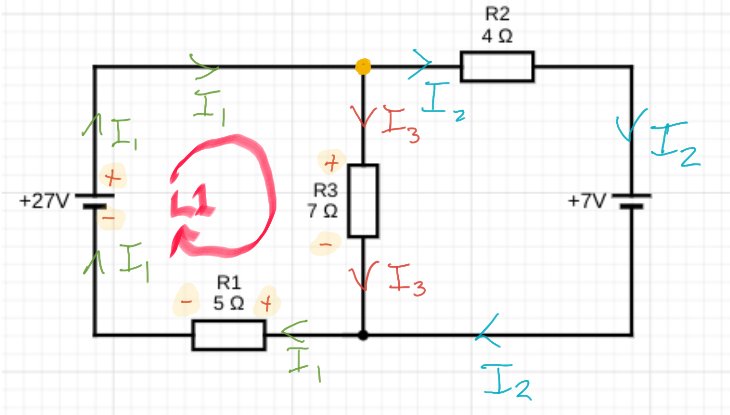

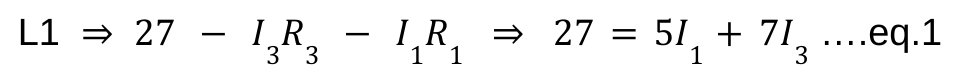

If we naively connected the ends of a coil to power supply, then the coil would make a partial turn and then lock in place, as shown below. When the coil is in the vertical position, then neither of the Fleming’s Left Hand Rule (FLHR) forces will produce a turning moment around the axis of rotation.

When the coil moves into this vertical position, two things would need to happen in order to keep the coil rotating continuously in the same direction.

- The current to the coil needs to be stopped at this point, because the FLHR forces acting at this moment would tend to hold the coil stationary in a vertical position. If the current was cut at this time, then the momentum of the moving coil would tend to keep it moving past this ‘sticking point’.

- The direction of the current needs to be reversed at this point so that we get a downward FLHR force acting on side X and an upward FLHR force acting on side Y. This combination of forces would keep the coil rotating clockwise.

This sounds like a tall order, but a little device known as a split ring commutator can help here.

One (split) ring to rotate them all

The word commutator shares the same root as commute and comes from the Latin commutare (‘com-‘ = all and ‘-mutare‘ = change) and essentially means ‘everything changes’. In the 1840s it was adopted as the name for an apparatus that ‘reverses the direction of electrical current from a battery without changing the arrangement of the conductors’.

In the context of this post, commutator refers to a rotary switch that periodically reverses the current between the coil and the external circuit. This rotary switch takes the form of a conductive ring with two gaps: hence split ring.

Tracking the rotation of a coil through a whole rotation

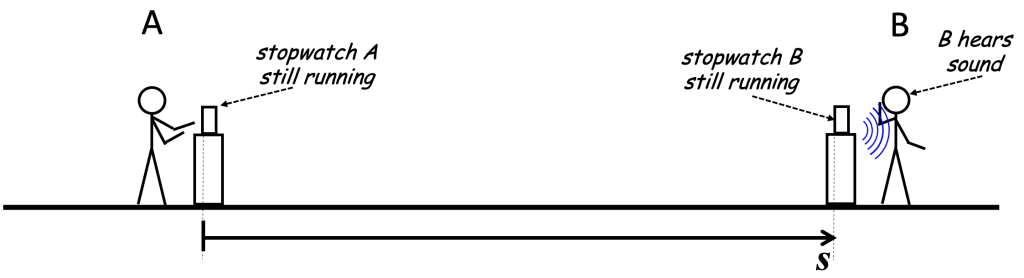

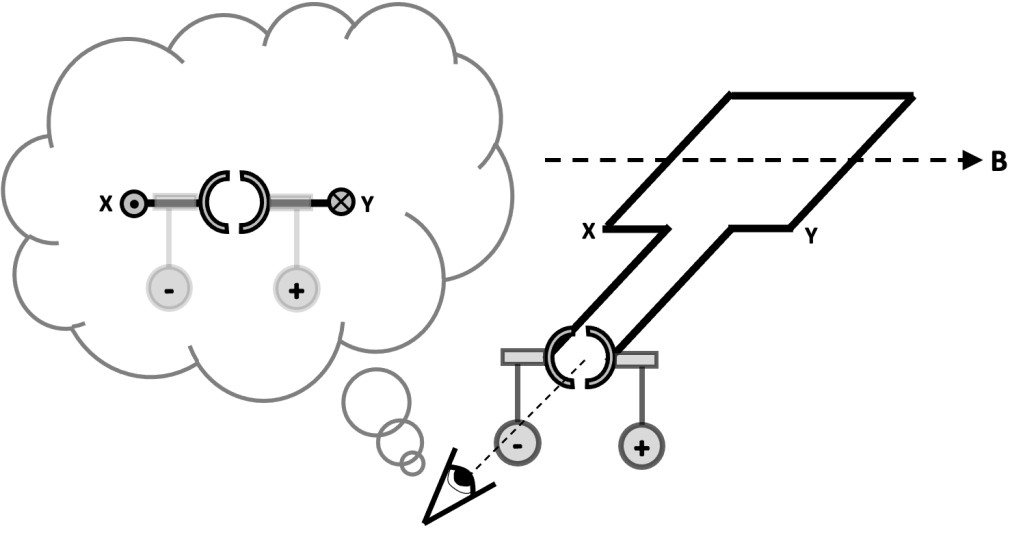

In this picture below, we show the coil connected to a dc power supply via two ‘brushes’ which rest against the split ring commutator (SRC). Current is flowing towards us through side X of the coil and away from us through side Y of the coil (as shown by the dot and cross 2D version of the diagram. This produces an upward FLHR force on side X and a downward FLHR force on side Y which makes the coil rotate clockwise.

Now let’s look at the coil when it has turned 45 degrees. We note that the SRC has also turned by 45 degrees. However, it is still in contact with the brushes that supply the current. The forces on side X and side Y are as noted before so the coil continues to turn clockwise.

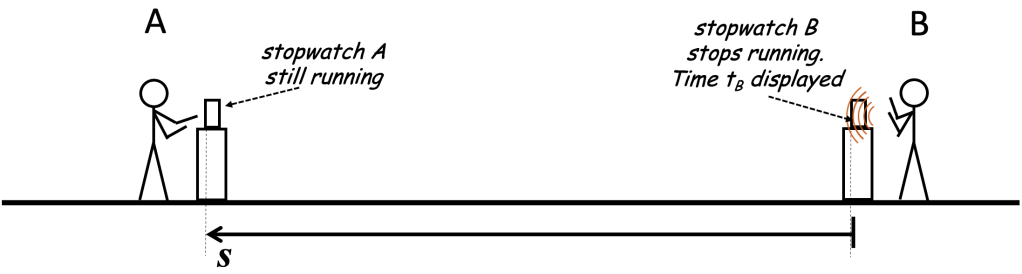

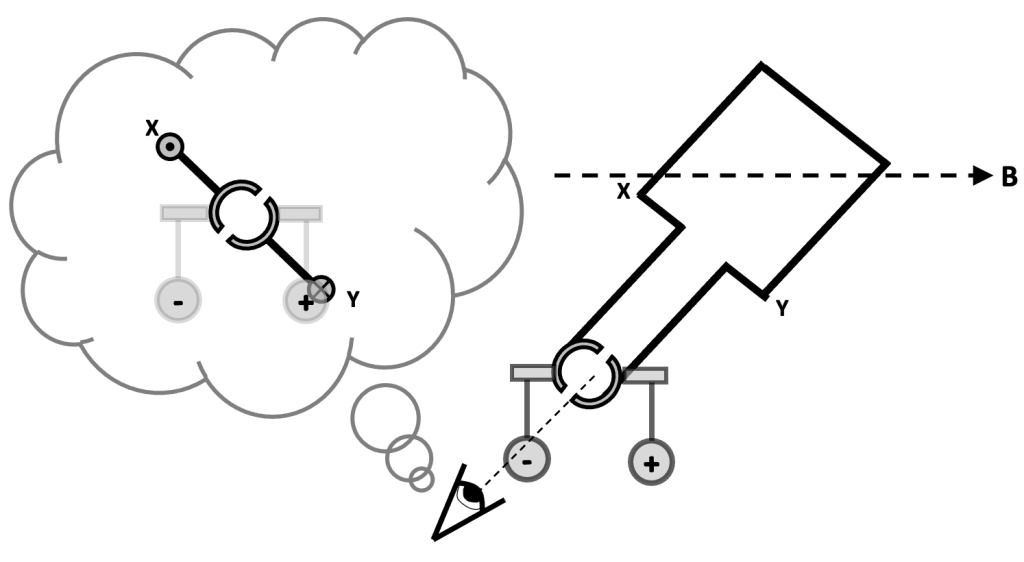

Next, we look at the situation when the coil has turned by another 45 degrees. The coil is now in a vertical position. However, we see that the gaps in the SRC are now opposite the brushes. This means that no current is being supplied to the coil at this point, so there are no FLHR forces acting on sides X and side Y. The coil is free to continue rotating clockwise because of momentum.

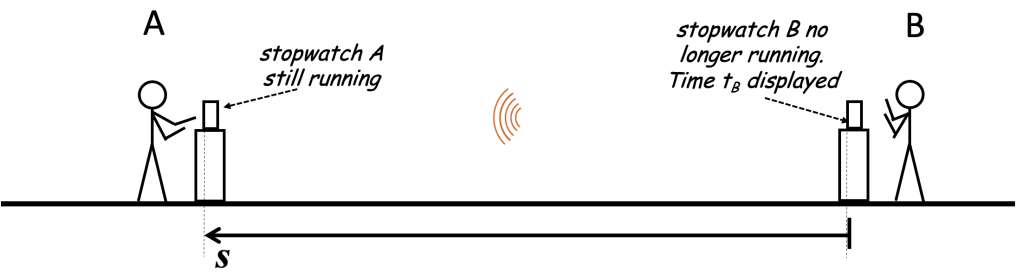

Let’s now look at the situation when the coil has rotated a further 45 degrees to the orientation shown below. Note that the side of the SRC connected to X is now touching the brush connected to the positive side of the power supply. This means that current is now flowing away from us through side X (whereas previously it was flowing towards us). The current has reversed direction. This creates a downward FLHR force on side X and an upward FLHR force on side Y (since the current in Y has also reversed direction).

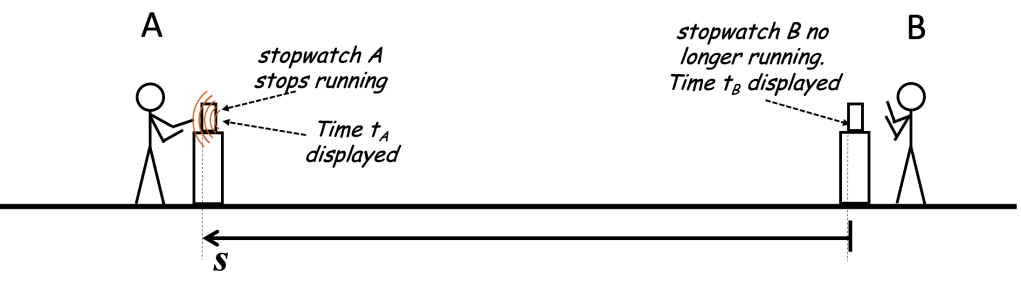

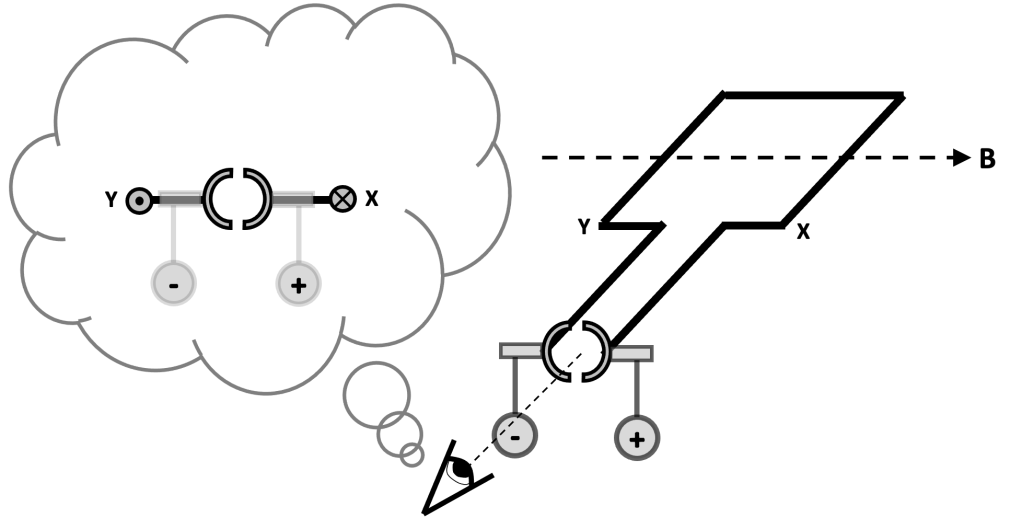

And a short time later when the coil has moved a total of180 degrees from its starting point, we can observe:

And later:

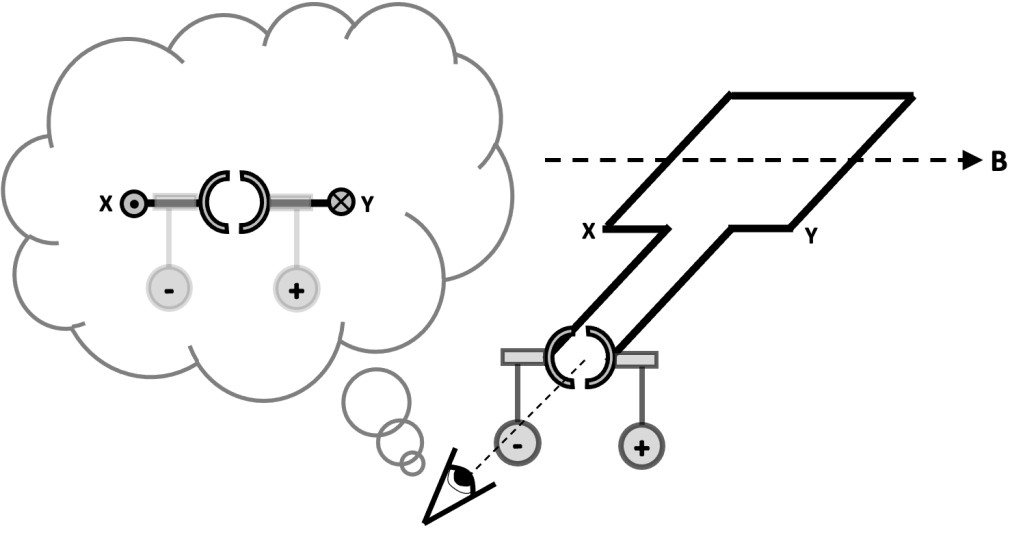

And later still:

And then:

And then eventually we get back to:

Summary

In short, a split ring commutator is a rotary switch in a dc electric motor that reverses the current direction through the coil each half turn to keep it rotating continuously.

A powerpoint of the images used is here:

And a worksheet that students can annotate (and draw the 2D versions of the diagrams!) is here:

I hope that this teaching sequence will allow more students to be comfortable with the concept of a split ring commutator — anything that results in a fewer split ring commuHATERS would be a win for me 😉