Nature abhors a change of flux.

D. J. Griffiths’ (2013) genius re-statement of Lenz’s Law, modelled on Aristotle’s historically influential but now debunked aphorism that ‘Nature abhors a vacuum’

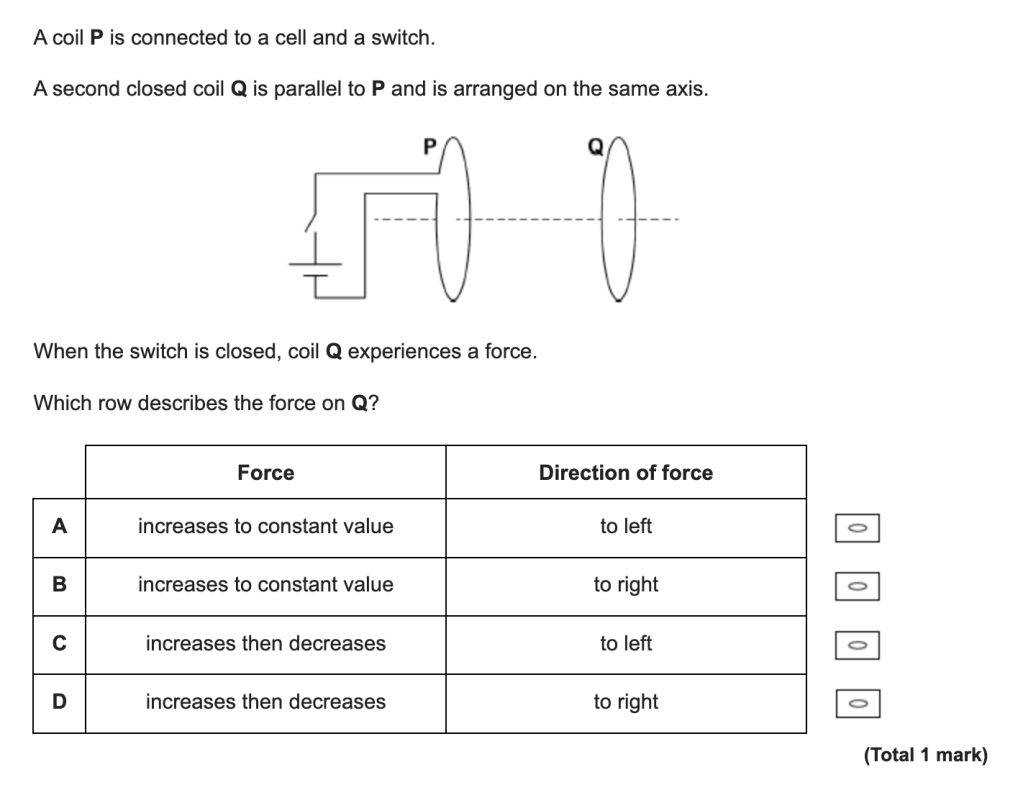

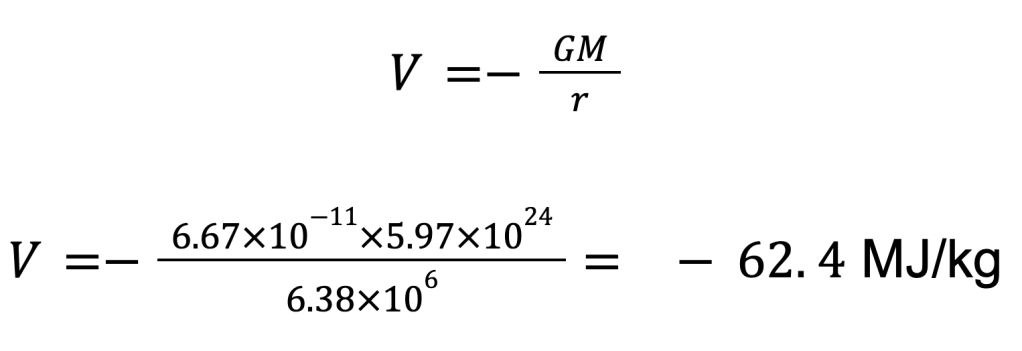

A student recently asked for help with this AQA A-level Physics multiple choice question:

This question is, of course, about Lenz’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction. The law can be stated easily enough: ‘An induced current will flow in a direction so that it opposes the change producing it.’ However, it can be hard for students to learn how to apply it.

What follows is my suggested explanatory sequence.

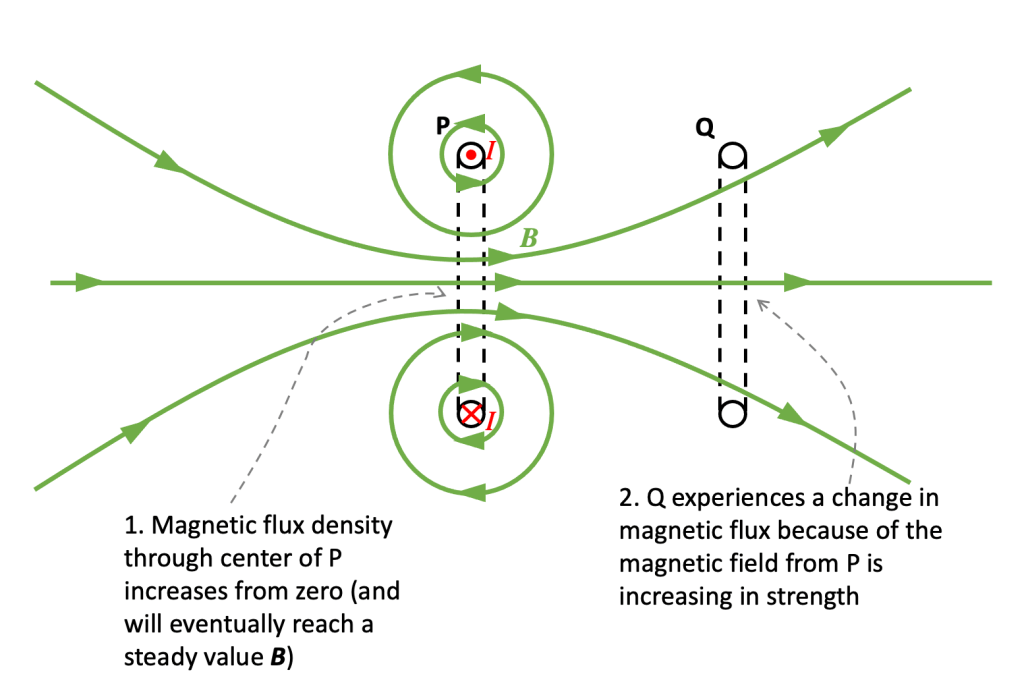

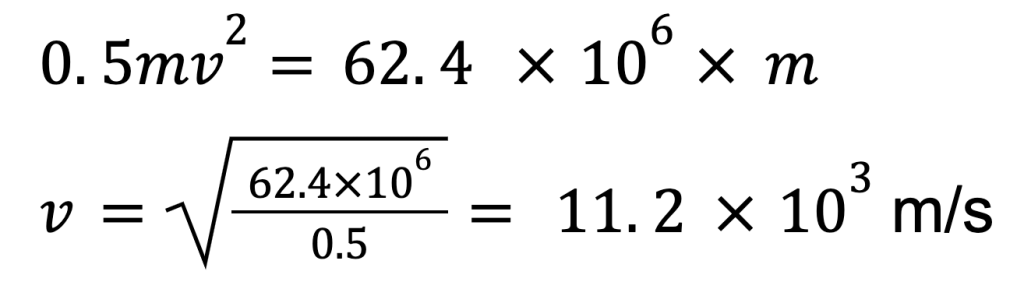

Step 1: simplify the diagram using the ‘dot and cross’ convention

When the switch is closed, a current I begins to flow in coil P. We can assume that I starts at zero and increases to a maximum value in a very small but not negligible period of time.

Step 2: consider the magnetic field produced by P

You can read more about a simple method of deducing the direction of the magnetic field produced by a coil or a solenoid here.

Step 3: apply Faraday’s Law to coil Q

Since Q is experiencing a change in magnetic flux, then an induced current will flow through it.

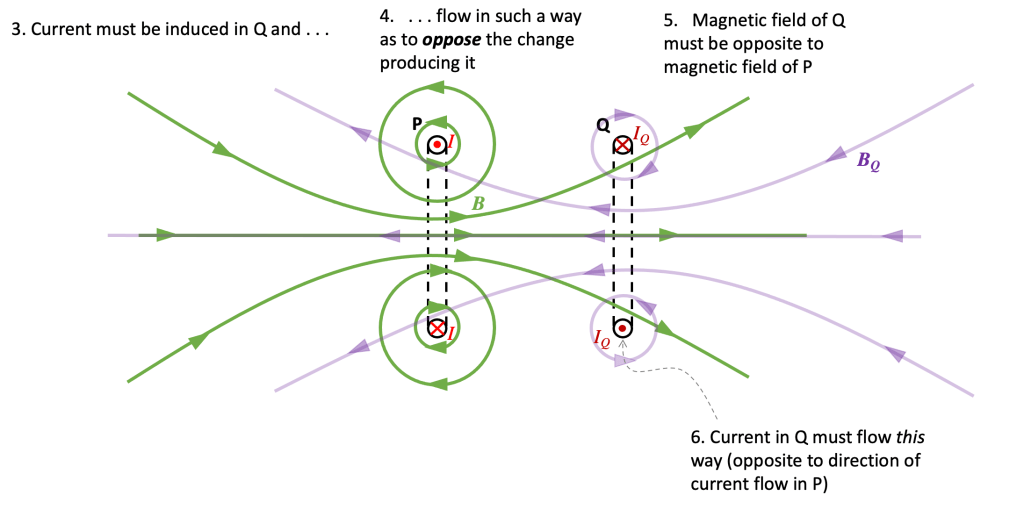

Step 4: apply Lenz’s Law to coil Q

The current in coil Q must flow in such a direction so that it opposes the change producing it.

Since P is producing an increasing magnetic flux through Q, then the current in Q must flow in such a way so that it tries to prevent the increase in magnetic flux which is inducing it. The direction of the magnetic field BQ produced by Q must therefore be opposite to the direction of the magnetic field produced by P.

Step 5: consider the polarity of the magnetic fields of P and Q

We can see the magnetic field lines of coil P produce a north magnetic field on its right hand side. The magnetic field of Q will produce a north magnetic field on its left hand side. Coil P will therefore push coil Q to the right.

It follows that we can eliminate options A and C from the question.

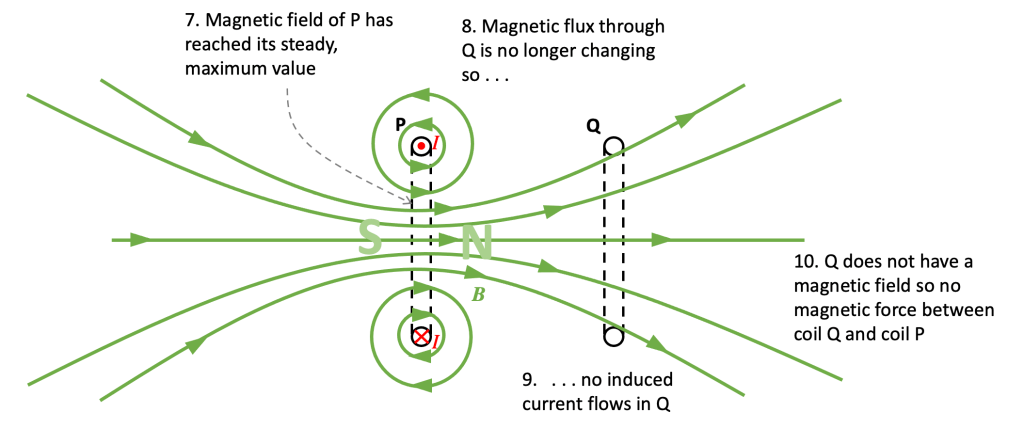

Step 6: What happens when the magnetic field of P reaches its steady value?

Because the magnetic field produced by coil P has how reached its steady maximum value, this means that the magnetic flux through coil Q also has a constant, unchanging value. Since there is no change in magnetic flux, then this means that no emf is induced across the coil so no induced current flows. Since Q does not have a magnetic field it follows that there is no magnetic interaction between them.

The answer to the question must therefore be D.

Step 7: check student understanding

For the alternative question, the correct answer of C can be explained by going through a process similar to the one outlined above.

- When the switch is opened, the magnetic flux through Y begins to decrease.

- A changing magnetic flux through Y induces current flow.

- Lenz’s Law predicts that the direction of this current is such that it opposes the change producing it.

- The current through Y will therefore be in the same direction as the current through X to produce a magnetic field in the same direction.

- The coils will attract each other.

- Eventually, the magnetic flux produced by coil X drops to a constant value of zero.

- Since there is no change in magnetic flux through Y, there is no induced current flow through Y and hence no magnetic field.

- There is no magnetic interaction between X and Y and therefore the force on Y is zero.

Conclusion

I hope teachers find this detailed analysis of a Lenz’s Law question useful! As in much of A-level Physics, the devil is not in the detail but rather in the application of the detail. Students who encounter more examples will have a more secure understanding.

Reference

Griffiths, David (2013). Introduction to Electrodynamics. p. 315.