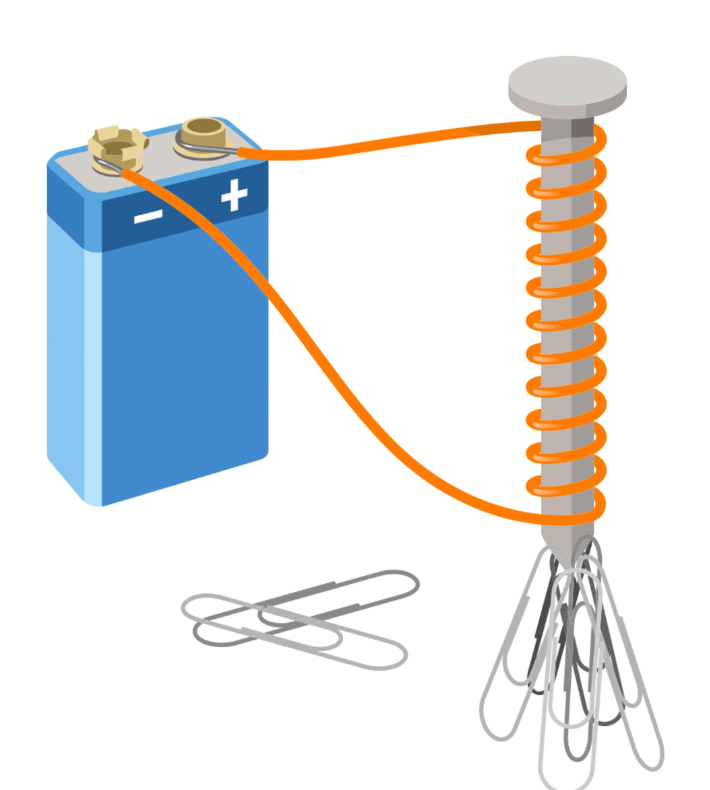

The Coulomb Train Model (CTM) is a helpful model for both explaining and predicting the behaviour of real electric circuits which I think is suitable for use with KS3 and KS4 students (that’s 11-16 year olds for non-UK educators).

I have written about it before (see here and here) but I have recently been experimenting with animated versions of the original diagrams.

Essentially, the CTM is a donation model akin to the famous ‘bread and bakery van’ or even the ‘penguins and ski lift’ models, but to my mind it has some major advantages over these:

- The trucks (‘coulombs’) in the CTM are linked in a continuous chain. If one ‘coulomb’ stops then they all stop. This helps students grasp why a break anywhere in a circuit will stop all current.

- The CTM presents a simplified but still quantitatively accurate picture of otherwise abstract entities such as coulombs and energy rather than the more whimsical ‘bread van’ = ‘charge carrier’ and ‘bread’ = ‘energy’ (or ‘penguin’ = ‘charge carrier’ and ‘gpe of penguin’ = ‘energy of charge carrier’) for the other models.

- Explanations and predictions scripted using the CTM use direct but substantially correct terminiology such as ‘One ampere is one coulomb per second’ rather than the woolier ‘current is proportional to the number of bread vans passing in one second’ or similar.

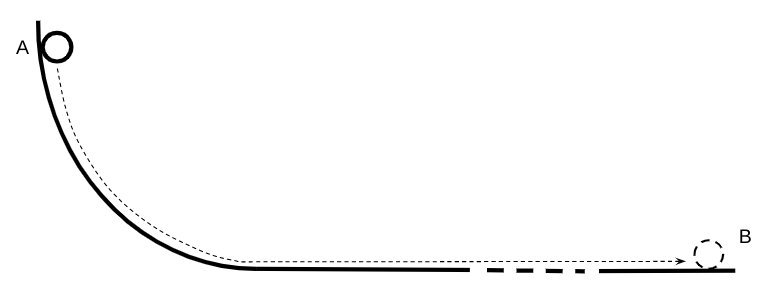

Modelling current flow using the CTM

The coulombs are the ‘trucks’ travelling clockwise in this animation. This models conventional current.

Charge flow (in coulombs) = current (in amps) x time (in seconds)

So a current of one ampere is one coulomb passing in one second. On the animation, 5 coulombs pass through the ammeter in 25 seconds so this is a current of 0.20 amps.

We have shown two ammeters to emphasise that current is conserved. That is to say, the coulombs are not ‘used up’ as they pass through the bulb.

The ammeters are shown as semi-transparent as a reminder that an ammeter is a ‘low resistance’ instrument.

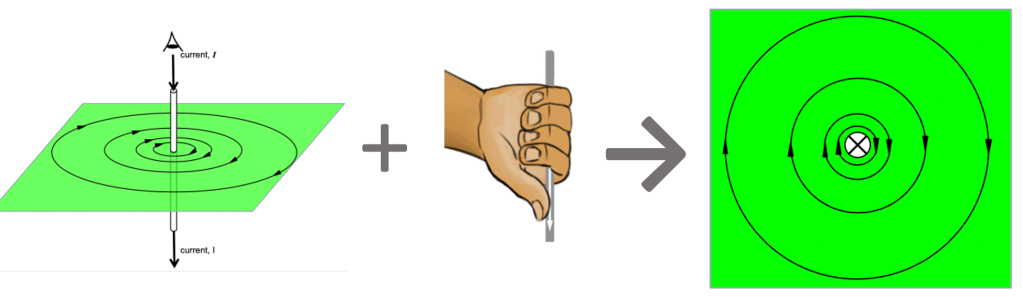

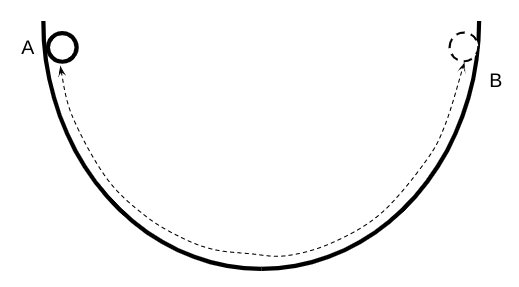

Modelling ‘a source of potential difference is needed to make current flow’ using the CTM

Energy transferred (in joules) = potential difference (in volts) x charge flow (in coulombs)

So the potential difference = energy transferred divided by the number of coulombs.

The source of potential difference is the number of joules transferred into each coulomb as it passes through the cell. If it was a 1.5 V cell then 1.5 joules of energy would be transferred into each coulomb.

This is represented as the orange stuff in the coulombs on the animation.

What is this energy? Well, it’s not ‘electrical energy’ for certain as that is not included on the IoP Energy Stores and Pathways model. In a metallic conductor, it would be the sum of the kinetic energy stores and electrical potential energy stores of 6.25 billion billion electrons that make up one coulomb of charge. The sum would be a constant value (assuming zero resistance) but it would be interchanged randomly between the kinetic and potential energy stores.

For the CTM, we can be a good deal less specific: it’s just ‘energy’ and the CTM provides a simplified, concrete picture that allows us to apply the potential difference equation in a way that is consistent with reality.

Or at least, that would be my argument.

The voltmeter is shown connected in parallel and the ‘gloves’ hint at it being a ‘high resistance’ instrument.

More will follow in part 2 (including why I decided to have the bulb flash between bright and dim in the animations).

You can read part 2 here.