Everyone in education loves data.

Or at least claims to. One sometimes wonders what would happen to the UK education system if a computer virus disabled every Excel spreadsheet overnight — h’mmm, perhaps someone should get in touch with those nice hacker people at Anonymous . . .

However, I digress. I wanted to share a recent epiphany that I’d had about data, particularly educational data. Perhaps it’s not much of an epiphany, but I’ve started so I’ll finish.

It came when I was listening to an interview on the evergreen The Jodcast (a podcast produced by the Jodrell Bank Radio Observatory). Dr Alan Duffy was talking about some of the new technologies that need to be invented in order to run the new massive Square Kilometre Array radio telescope (due to begin observing in 2018):

And then we have to deal with some of the data rates . . . essentially we recreate all of the information that exists on the internet today, and we do that every year without fail, it just keeps pouring off the instrument. And what you’re looking for is the proverbial needle in the haystack . . . how do you pick out the signal that you’re interested in from that amount of data?

— The Jodcast, October 2014, 18:00 – 21:00 min approximately [emphasis added]

The realisation that hit me was: it isn’t the data that should be centre stage — it’s the signal that’s contained within that data. And that signal can be as hard to find as the proverbial needle in a haystack, even without data volumes that are multiples of the 2014 Internet.

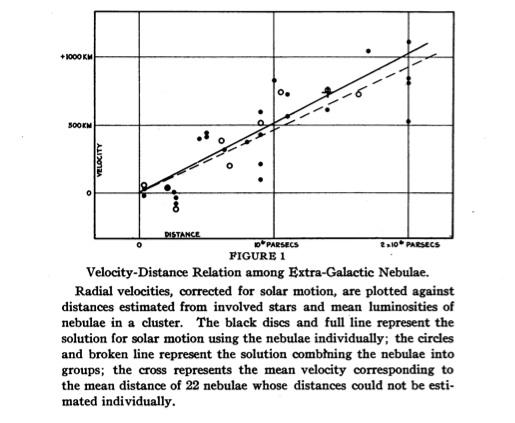

A simple example from the history of science: Edwin Hubble’s famous graph from 1929 that was one of the first pieces of evidence that we exist in an expanding universe. The data are the difficult and painstaking measurements made by Hubble and his colleague Vesto Slipher that are plotted as small circles on the graph.

The signal is the line of best fit that makes sense of the data by suggesting a possible relationship between the variables. Now, as you can see, not all the points lie on, or even close, to the line of best fit. This is because of noise — random fluctuations that affect any measurement process. Because Hubble and Slipher were pushing the envelope of available technology at the time, their measurements were unavoidably ‘noisy’, but they were still able to extract a signal, and that signal has been both confirmed and honed over the years.

In my experience, when the dread phrase “let’s look at the data” is uttered in education, the “search for a signal” barely extends beyond simplistic numerical comparisons: increase=doubleplus good, decrease=doubledoubleplus ungood.

The way we use currently use data in schools reminds me of SF author William Gibson’s coining of the term cyberspace (way back in the pre-internet 1980s) as the

consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legimate operators . . . a graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system

— William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984)

In my opinion, almost the whole statistical shebang associated with UK education, from the precipitous data-mountains of the likes of RAISEOnline (TM) to the humblest tracking spreadsheet for a department of one, is actually nothing more than a ‘consensual hallucination’.

The numbers, levels and grades mean something because we say they mean something. And sometimes, it is true, they can tell a story.

Let’s say a student has variable test scores in one subject over a few months: does this tell us something about the child’s actual learning, or about possible inconsistencies in the department’s assessment regime, or about the child’s teachers?

My point is that WE DON’T KNOW without cross referencing other sources of information and using — wait for it — professional judgement.

I believe that the search for a signal should be central to any examination of data, and that this is best done with a human brain through the lens of professional experience. And, given the inevitability of noise and uncertainty in any measurement process, with a generous number of grains of statistical salt.